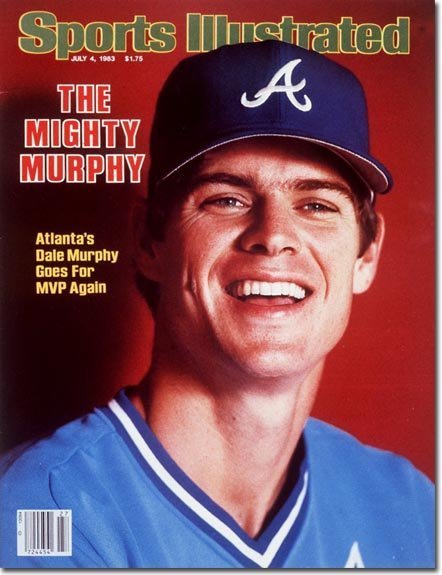

Nice guys finish first. Dale Murphy of the Atlanta Braves proved that last year. He also proved that nice guys can drive in 109 runs, hit 36 homers and bat .281. And what did he do in the time between the end of the 1982 season and the announcement five weeks later that he was the National League MVP? He went to the Instructional League to work on his hitting.

Here's a guy who doesn't drink, smoke, chew or cuss. Here's a guy who has time for everyone, a guy who's slow to anger and eager to please, a guy whose agent's name is Church. His favorite movie is Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life. He's a wonderful ballplayer.

Here's a guy who's chasing the Triple Crown. Through last Sunday, he shared the National League lead in home runs with 19, ranked second in RBIs with 55 and fourth in batting average at .326. His 69 runs put him on course to challenge the modern league record of 158 set by Chuck Klein of the 1930 Phillies. Here's a guy who failed as a catcher but ended up winning a Gold Glove in 1982 while playing centerfield. Here's a guy who's 6'5", 220 pounds, and he's going to steal at least 30 bases this year. "He's scary," says Reds manager Russ Nixon. "Do they have something above MVP?"

And here's a guy who, after almost every home run, says something like, "Well I just happened to get good wood on the ball, and the wind was blowing out to rightfield tonight. . . ." When asked if he feels he has improved on his MVP play of a year ago, Murphy will say, "I can't say for sure, I've been a little lucky this year. I hope I'm progressing." Here's a guy who is Jimmy Stewart--the actor, not the former utility player.

"Aw, he's just a guy," says Murphy's friend and foil, Atlanta Catcher Bruce Benedict. "Except when he eats. Then he's a superstar."

Like the mole on his right cheek, even his faults have their charms. While it's true that Murphy has never met a doughnut he didn't like, he carries not an ounce of fat on his sculpted frame. He's occasionally late to practice only because he's giving his time to someone else. Says Manager Joe Torre, "I've had to fine him, but many times I don't know he's been late until I find his money on my desk." And it's because Murphy has so many friends in so many cities that he's won the coveted Ticketron Award, given to the Braves player who uses up the most passes, four years in a row.

"Believe me, I have many more faults than that," says Murphy. "I don't want to give people the impression that I'm an almost perfect human being."

Now it can be told. In the early winter of 1978, Murphy was pulled over for speeding. It happened on the campus of Brigham Young University, which Murphy, a Mormon since 1975, was attending briefly. He was doing 35 in a 25-mph zone. Where was the fire? "Well, I was late for a speech before a church group," Murphy says.

If Murphy sound too good to be true, rest assured that he is for real. "There is nothing, absolutely nothing fake about him," says teammate Jerry Royster. Murphy certainly has been proving this year that he's for real on the field. He wasn't an overwhelming choice for MVP last year, and he would be the first to defend his doubters. "I really owe the award to my teammates," he says. "If we hadn't won the division, I wouldn't have won the award." Of course, the Braves themselves were thought to be something of a fluke last year when they won the National League West title. But as of Sunday, Atlanta was 43-29, matching its 1982 pace; the only trouble with that was L.A. was eight games better than its pace. No other team in the majors had a better record, which left the Braves second in both the division and the big leagues.

There are two sure signs that Murphy has arrived. Boos now greet him on the road, although they are more respectful than nasty. And the mythologizing of Murphy is under way. Before a home game against San Francisco on June 12, Murphy visited in the stands with Elizabeth Smith, a six-year-old girl who had lost both hands and a leg when she stepped on a live power line. After Murphy gave her a cap and a T shirt, her nurse innocently asked if he could hit a home run for Elizabeth. "I didn't know what to say, so I just sort of mumbled 'Well, O.K.,' " says Murphy. That day he hit two homers and drove in all the Braves' runs in a 3-2 victory.

Even his home runs are nice. They're often looping, opposite-field line drives that just happen to go over the fence. Of his 19 homers this year, all but four have been to center or rightfield.

Here's a sampler of what opponents think of Murphy:

Astro catcher Alan Ashby: "He's the best player in the game today."

Cubs Pitching Coach Billy Connors: "He's the best I've ever seen, and I've seen Willie Mays. I watch almost all the Atlanta games on cable television, and I've seen Murphy win games every way there is, a base hit in the ninth, a home run, a great catch, beating the throw to first on a double play. I've never seen anything like him before in my life."

Phillies Third Baseman Mike Schmidt: "I don't see why I should talk about another player hitting 100 points better than I'm hitting."

And here's what some teammates think of Murphy:

Pitcher Phil Niekro: "People keep looking for words to describe him. Well, there aren't enough good words or words good enough."

Royster: "If you could improve Andre Dawson, he would be Dale Murphy."

Torre: "All he does is play baseball better than anyone else."

Benedict: "He's overrated. He's also got big feet."

Benedict is right about those feet, which are size 13, but he's kidding about the overrated part. Actually, some people did think Murphy was overrated last year, especially after he slumped late in the season when Bob Horner, who bats behind him in the fourth or fifth position depending on the pitcher, left the lineup with an injury. "Murph did put a lot of pressure on himself," says Torre. "And good as he was, I saw ways to improve his hitting."

At first Murphy was surprised when Torre suggested he go to the Instructional League in Sarasota, Fla. with all the youngsters. But he readily agreed to combine the instruction with a planned trip to Disney World with his two sons and wife, Nancy, who was then pregnant with their third son. "I thought it was a compliment that Joe wanted to take the time and go down there and work on a few things with me," says Murphy.

So, for five days, Murphy dressed with the Atlanta organization's kids, took 30 minutes of batting practice with Torre and Coach Bruce Dal Canton and talked hitting. "I think we're seeing the fruits of that work this year," says Torre. "Take the other night. Dale beat the Dodgers with a sacrifice fly in the ninth off Tom Niedenfuer. Niedenfuer pitched him very well, and last year Dale would've struck out in that situation. That's the big difference this year--he's become a much better hitter with two strikes on him."

The facts of Murphy's life are that he was born to Charles and Betty Murphy in Portland, Ore. on March 12, 1956. He grew up in Portland, except for a brief time in Moraga, Calif. when his father, then a sales executive for Westinghouse, was transferred there. Dale played for Woodrow Wilson High in Portland. He signed a letter of intent to go to Arizona State, but decided to try pro ball right away when the Braves made him their first pick in the June 1974 draft.

Jack Dunn, a friend of the Murphy family, was Dale's coach in both high school and American Legion ball. Now the coach at Portland State, Dunn recently visited Murphy in San Francisco when the Braves were playing the Giants. "I always knew he was something special," Dunn says. "I know it's just a coincidence, but did you know that the man who discovered Babe Ruth was also named Jack Dunn?"

In 1976, though, Murphy was being touted as the next Johnny Bench. He had the prerequisites: a live bat and a rifle arm. He also had a new religion, and he wanted to serve a two-year mission, as young members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints frequently do. Ted Turner, owner of the Braves, got wind of this and asked Murphy's parents if he could talk to Dale. They said yes, but be careful, Dale's very serious about this. So Turner reached Murphy in Portland and the first thing he said was, "What's all this Mormon stuff? If you need to make converts, I'll let you work on me and my five kids."

Turner didn't talk Murphy out of his mission, but some officials of the church, including a former minor league pitcher named Paul Dunn, convinced him that he could serve while playing. But then something happened. Murphy began to develop a mental block about throwing to second base. He would either hit the pitcher, even if he were crouching on the mound, or he would throw the ball into the outfield. As his father told him, "One thing's for sure, Dale. Nobody will be stealing centerfield on you."

Murphy now looks back on that time with humor. "I think they put me in centerfield because it's as far away from home plate as possible," he says. Actually, the Braves initially tried Murphy at first base, but he couldn't make throws from there either. On March 12, 1980 Bobby Cox, then the Atlanta manager, sent Murphy to leftfield. Suddenly he could throw again.

Like George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) in It's A Wonderful Life, Murphy was given a second chance. In the move a despairing Bailey is about to leap off a bridge when his guardian angel, Clarence Oddbody, appears. While talking Bailey out of suicide, Oddbody says, "You see, George, you've really had a wonderful life. Don't you see what a mistake it would be to throw it away." Murphy, literally, almost threw his career away.

"I never got as low as Jimmy Stewart did in the movie," says Murphy, "but there was a time when I didn't think I'd be able to stay in the minors, much less play in the majors. I couldn't throw, and it was very frustrating. I had all this God-given talent, but all of a sudden I couldn't play. I tried to keep it in perspective and tried not to let it affect my relationships with people. Fortunately, I came through. But I realized that even without baseball, it's a wonderful life."

As soon as Murphy moved to the outfield, the throwing phobia disappeared, just like that. In 1980, while performing in unfamiliar territory, mostly centerfield, he hit .281 with 33 homers and 89 RBIs. In '81, for reasons neither Murphy nor anyone else can explain, his production fell off sharply. Turner wanted to cut Murphy's '82 salary 20% to $320,000, but Dale and his agent, Bruce Church, negotiated the Braves back up to $360,000, plus $40,000 in bonuses, all of which Murphy cashed in on. With free agency looming after this season, Murphy and the Braves agreed in February to a five-year, $8 million contract, making him the fifth-highest-paid player in baseball. The contract was also a boost to the LDS church, because Murphy tithes the usual 10% and contributes additionally to other church funds. He did allow himself the luxury of a new silver Corvette.

Murphy apologizes for not being more colorful, though he's extremely generous with his time. "I wish he was more selfish," says Benedict. "But then he wouldn't be Dale Murphy." Often a teammate will have to pull Murphy away from an interview session and tell the interrogators, "Sorry, Dale has to go to batting practice now."

The Braves like to tell stories about his eating. According to Second Baseman Glenn Hubbard, "He once complained that the watermelon in the clubhouse was rotten. That was after eating five pieces of it." Says Royster, "I've seen him order everything on the menu except THANK YOU FOR DINING WITH US."

His insatiable need for tickets also makes him a clubhouse target. "Hey Dale," shouts Benedict. "How come you don't say, 'Hi, how are you, how you feeling' anymore? You just say, 'Can I have your tickets?' Then you go have a doughnut." In truth, Murphy is very solicitous when he asks a teammate for passes.

Murphy does get upset every so often. Says Hubbard, "I remember he once got mad at the opposing pitcher for showing up his catcher. The catcher had dropped a throw from the outfield, and the pitcher was glaring at him. Dale told our pitchers he never wanted to see any of them do that to one of our catchers."

"I saw him get mad once," says Torre. "It was this year in San Diego, where the fans are right on top of the dugout. This one fan was screaming obscenities at us. Well, Dale starts getting red, then gets on the top step, leans on the roof of the dugout and says, 'You can shout whatever you want. Just don't cuss.' I think the entire stadium fell silent."

The one thing Murphy can't abide is women journalists in the locker room. Last year two female writers walked into the Braves' clubhouse as Murphy was being interviewed in his undershorts. He excused himself, put a jersey around his waist and went up to the women. "You just can't come in here, ladies. It's just not right," he said. Having been confronted by Jimmy Stewart, they retreated. Right or wrong, Murphy's stance is a matter of honor to him.

It's as if he stepped out of the past or, at least a Frank Capra movie, to take his place in centerfield for the Atlanta Braves. And every time he hits a home run, he'll say he just happened to get good wood on the ball, and the ball just happened to carry. . . .